Tim Diacono

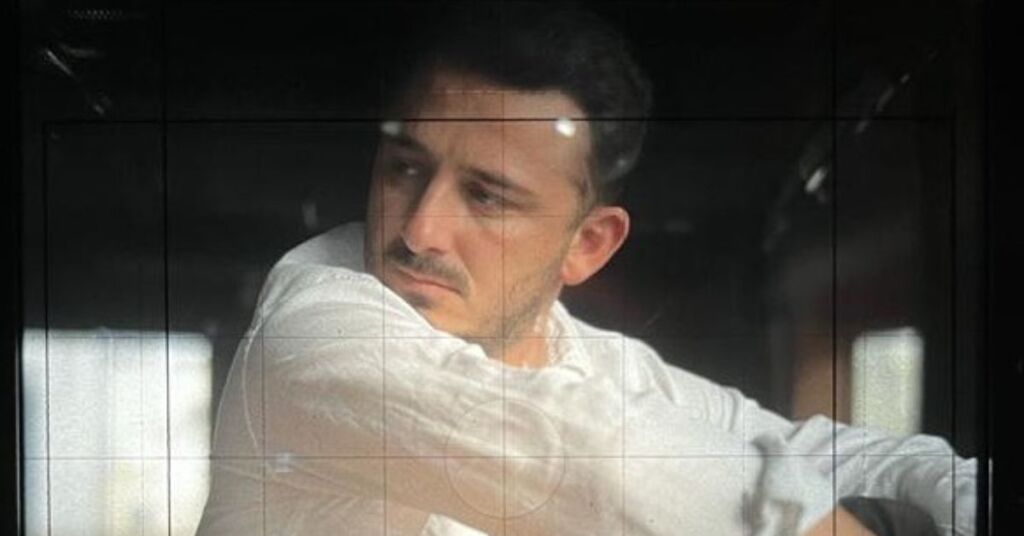

Born and raised in Malta, Bonnici moved to the UK to seek his architectural fortune when he was only 16 years old.

Upon completing his studies, he worked on a thesis focusing on the Paspels School, a striking piece of architecture in a tiny Swiss village with fewer than 500 inhabitants, mostly elderly people.

There, Bonnici got to meet world renowned Swiss architect Valerio Olgiati, the mind behind the School, who is well-known for his “non-referential” style of architecture, which seeks to create buildings that are meaningful to their surroundings in and of themselves.

What followed was a two year internship under Olgiati , and the Swiss architect was clearly impressed by what he saw, because two weeks after his internship was over, he called the Maltese architect to offer him a full time job.

Bonnici was tasked with leading Olgiati’s international projects, with his knowledge of the English language – as well as his architectural talent – considered an advantage.

Within a few months, Bonnici got to collaborate with Olgiati on his first major projects after the French luxury fashion house Céline got in touch with the Swiss architect to design a flagship store in Miami. Bonnici spent a few weeks at Céline’s Paris headquarters to get inspiration, and a year and a half later, the Miami store was complete – a stunning two-storey building whose facade, walls and floors were decked in Brazilian Pinta Verde marble.

Fresh from the success of the Céline store, Bonnici’s stock grew and he was entrusted with other major international projects – including a winery in Tuscany, a concrete tower and a house in Peru, and a competition to redesign the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

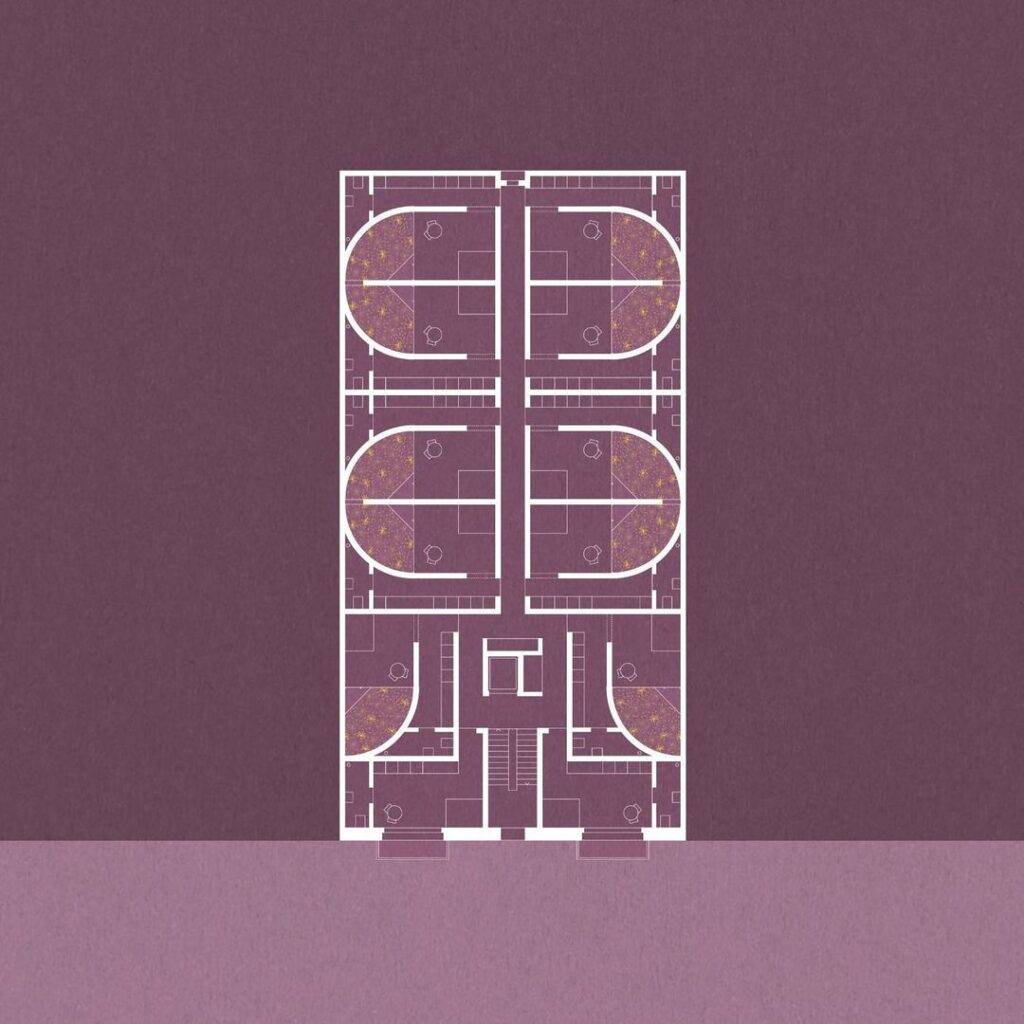

He also helped Olgiati design a visitors’ centre leading to the UNESCO Pearling Path in the old Bahraini capital of Muharraq, a massive project that had been entrusted to him by the Arab state’s Ministry of Culture.

The end result was an earth-coloured canopy as large as a football pitch, supported by a “forest” of columns to create an urban “living room” where people could circulate freely.

Although Bonnici and his team were under a tight schedule and only had six-seven months to complete the project, they managed to produce an iconic piece of architecture that has been credited with transforming the spirit of Muharraq.

Elsewhere, Bonnici was entrusted by Olgiati with leading his firm’s presence at the Venice Biennale, a massive global festival of art and architecture.

The Maltese architect’s work even caught the eye of the famous rapper Kanye West.

Bonnici recounted how West’s fashion brand Yeezy had sent an email to Olgiati at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, praising his work and requesting a general meeting.

During an online meeting with West, Olgiati and Yeezy’s architects, Bonnici found out that the rapper had just purchased a ranch in Wyoming and wanted to build an underground shelter where he could disconnect from the world.

They spoke for hours about this project, and West pitched further ambitious ideas, including a city in Atlanta where cars would never be visible at street level.

Bonnici developed a close personal relationship with West, who even sent him a sneak peak of his 2021 album Donda.

“I loved him, he’s the best client I have ever had,” Bonnici recounts. “He’s very intense, just as many creative people are… it comes with the territory. He was creatively naive in the best way possible.”

When West spent a few days in Switzerland, West got to meet him as well as his new partner, the Australian architect and model Bianca Censori.

Bonnici was impressed by Censori, and when he eventually started lecturing at the University of Malta, he invited her to deliver an online lecture about primitive futurism.

After several years of working with Olgiati, Bonnici moved back to Malta where, besides lecturing, he teamed up with fellow architect Karl Ebejer.

“It happened very organically,” he explained. “I had been on a hiatus for six months, which was a time of introspection for me when I was refiguring what I like and whether this was the field I wanted to go down.”

“I met up with Karl and it turned out he had this amazing site and a client with a very cool brief. We worked on it for two-three weeks and the client loved the concept. Karl and I had already been intellectually and creatively dating for around two years and it had come to a point where it made total sense to partner up, collaborate long-term, and create our own nimbus here.”

Along with a small team of architects and interns, Bonnici and Ebejer have already designed a number of Maltese residential projects, including in Santa Venera and St Julian’s, and are working on international projects such as a house in Mexico and a store in Vienna.

“I like living in Malta and I love the people here,” Bonnici says. “Even though many people find it tough to live here, I see it as a very effective place to test out my ideas while being far away from the people who have influenced me.”

Influence by Olgiati’s non-referential style, Bonnici is seeking to create a “new language of architecture”, that is Maltese at its core without trying to define the island’s image.

“We’re not trying to make something political; our role is cultural,” he says. “A lot of architects locally are seen more as lawyers than as creatives, and I want to shift to the concept of the architect as a leader, an inventor, and a definer of what culture is.”

“I fell in love with architecture in Malta again.”

Bonnici has learned that creative naivety is a crucial skillset for architecture, as it is for all creative arts.

“Even some of the best architects in the world have had buildings demolished before they were even built, but you cannot grow cynical, bitter or angry,” he says.

“Finishing a building is like climbing Mount Everest every single time – you always forget about the cultural frostbite.”

“I am lucky to be a naturally optimistic and creatively naive person and the potential of discovering something new, big or small, is what motivates me to wake up in the morning.”

“Fundamentally, creatives have to exceed limits and push boundaries because you’re not going to discover anything new with conventional ideas. Remember that what seems normal today was an invention 200 years ago.”

You Might Also Like

Latest Article

The World Ahead: What 2025 Holds for the Global Economy

As we step into 2025, the global economy stands at a fascinating crossroads. Here are the key trends, market realities, and sectoral shifts likely to define the year ahead. 1.Global Growth: A Steady Yet Uneven Recovery The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts global growth at around 3% for 2025, marking a slight dip from … Continued

|

24 December 2024

Written by Tim Diacono

Top 10 Financial Milestones of 2024

|

21 December 2024

Written by Hailey Borg

Building a Vision for Real Estate Excellence: Jeremy Cassar and ERA Real Estate Malta

|

20 December 2024

Written by Hailey Borg